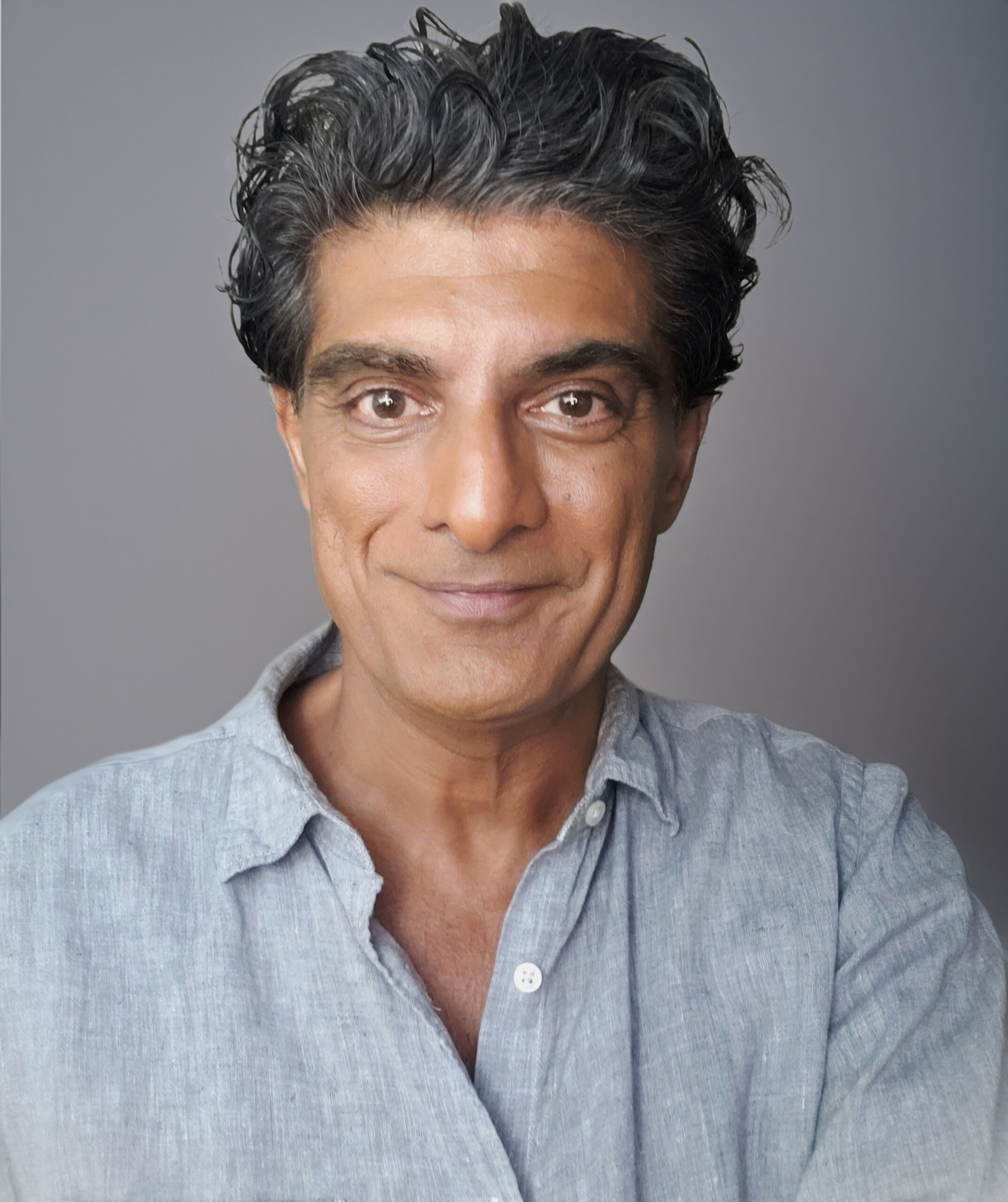

TIFF 2024: Our Chat With Writer-Director-Star Srinivas Krishna On The 4K Restoration Of His Hidden Canadian Classic ‘Masala’

Entertainment Sep 18, 2024

Filmmaker Srinivas Krishna tells us about bringing his funny, poignant, wildly creative debut to a new generation via 4K restoration

TIFF is known as one of the world’s most prestigious showcases for new films before they make their way to a larger audience — yet in its celebrations the festival looks not just to the future, but to cinema’s storied past.

Partnering with Telefilm Canada’s “Canadian Cinema — Reignited” initiative to digitize and restore culturally significant movies from years gone by, in 2024 TIFF presented a 4K restoration of writer-director Srinivas Krishna’s 1991 debut, Masala.

Set in Toronto, the film follows a troubled young man named Krishna (played by the filmmaker himself), who lost his family in the 1985 Air India terrorist attack and, ridden with survivor’s guilt, collapsed into a life of heroin addiction. Now in recovery, he’s determined to raise enough money to move out west and reinvent himself. To do so, however, he needs the help of his mother’s family — particularly his wealthy uncle (Saeed Jaffrey). And in the process of mending fences and reintegrating into his relatives’ lives, our troubled hero is forced to confront his unresolved trauma and piece together a profoundly fragmented identity. All the while, Krishna’s fate is presided over by a Hindu god who bears his name (also played by Saeed Jaffrey).

Heavy though that all may sound, Masala is a giddy mix of irreverent comedy and poignant drama, glorious Bollywood bombast and gritty Canadian indie — exploring the complexities of immigrant identity within a so-called “multicultural” nation.

Ahead of this year’s fest, ANOKHI LIFE spoke with Krishna about bringing Masala to a new generation, and how that three-decades-old story is both a snapshot of a particular moment in Canadian history, and still inherently relevant for the immigrant experience of today.

Matthew Currie: Is it a singular experience to revisit something you created decades ago?

Srinivas Krishna: It’s something I’m still processing, because it was a unique experience making the film the first time around. It was my first feature film. For many of the people who worked on it, it was the same. We were very young, we were all just starting out, and we knew that we were making something special and unique. We gave all that we had at that time, without really knowing what would happen, until audiences started seeing it and it really found its home, and kind of built a new audience that people didn’t realize existed — which was an audience of people that, back in back in 1991 and ’92, were more cosmopolitan and had more diverse tastes than Hollywood mainstream cinema had addressed. It was a time when indie films were just starting out. It was really a different era.

MC: Just you, Tarantino and Kevin Smith!

SK: [Independent cinema] was just starting out, and of all that group, I came from a very different place, which was cross-cultural, South Asian, immigrant, the child of immigrants. So today, when I go back, it’s unique all over again — because who knew that this would happen, that the film would be recognized as a classic of Canadian cinema, that it would mean that much to the culture?

When I made the film, it was like we just gave birth to this child and we were shepherding it into the world. Thirty-three years later, it’s like meeting your kid who’s all grown up and you haven’t seen them for awhile and you go, “Oh, look at you. You don’t belong to me anymore. You belong to the world now and to yourself, and you have your own story.” It’s a story that belongs to audiences, at the end of the day . . . Making a work and having it go out into the world is a process of weening yourself off of it, and recognizing that I am separate from the work at some point.

MC: Can you talk us through your character’s journey? Who is Krishna at the start of the film vs. who is he at the end?

SK: Well, the character I play, he’s someone who’s going through what we call today post-traumatic stress disorder. In those days, we didn’t have those words. He’s got a huge piece of survivor’s guilt. He was supposed to be on a flight going back to India that was blown up, in which his family perished. He didn’t get on the plane [due to] an argument that was probably ongoing with his family, particularly his dad. He didn’t want to return to India and go on a family vacation with them — and he lost them. That led him on a journey into drug addiction, and when we meet him, he’s trying to get on the straight and narrow. He’s got a plan. He wants to get some money from his old girlfriend and go to Vancouver, of all places — which was always, for those of us growing up in Toronto, the “West.” Freedom. Self-invention. A place far away from everyone you knew.

It doesn’t work out, so he goes to his family. That’s his state: I’ve got a plan and I’m really going to use the people around me, whoever I can, to execute this plan. He’s very much like an addict. He’s driven by his needs, not very conscious of other people . . . I think his growth is, as he spends time with his family, and particularly as he meets the character Rita, who is played by Sakina Jaffrey, he starts confiding what’s happening with him, and she challenges him. In that process, I think he comes to terms with what he lost, and believes that, with Rita, he can find a way forward and find a place of belonging. Which, of course, gods and destiny have a different fate in store for him.

MC: What exactly did this restoration process entail?

SK: What happens when you restore a film to 4K is you take either the original 35mm negative or a very high-quality print, and the sound, and you transfer it to digital. In that process is a lot of colour correction that has to happen, so the film maintains its integrity as it’s transferred to a high-resolution digital format. It goes from a chemical, organic material to pixels. That was supervised by our cinematographer, Paul Sarossy, who is a master of light. So, it looks gorgeous. The second part of that is attaching all of the subtitles and captions — none of which we really had to that degree 33 years ago. So, a lot of that was produced; it was taken from DVD releases in the past and updated and making sure that those are correct. And then finally, it’s cleaning up. Getting the dust and all of that off the digital so that it looks pristine.

It’s going to look amazing, and most importantly it’s going to give the film a second life in online streaming, which it hasn’t been able to enjoy for a decade now.

MC: From a creative, storytelling standpoint, re-evaluating your work three decades later, what do you feel when you look at the movie?

SK: I can’t help but look at that film and just laugh. Because it’s a very funny film, and you see things that you can’t believe you’re watching. I think we have to remember that the film is, for its time, very politically incorrect. All those things that we might think somewhere in the back of our mind and censor ourselves, the film actually says. You say, “I can’t believe they’re going to go there.” And it goes there.

MC: Masala very much engages and dissects the concept of multiculturalism. Have your thoughts on that subject evolved over the years?

SK: The film came out, and it was really the product of Canada’s first completely multicultural generation. I came here as a kid from India in 1970 — I must’ve been six or seven years old — and started Grade 1. And the film was made after 20 years of living under this official policy of multiculturalism, which was new. That experience was a first-of-its-kind experience. People hadn’t really had that experience anywhere else. Really, Canada was unique with that policy. What it meant for me and for many others was that, because we were told you keep your identity, you don’t have to “assimilate” and here’s money from the government to help you teach your kids the language and your traditions — at home, you had one kind of life, which was supposed to be your heritage. Outside of home, you were just like everybody else — you were just like your peers, like your buddies. There was only one group of people that didn’t have this experience, where what was going on at home was much the same as what was going on outside, and those were the people already here. You become keenly aware of this.

Within this thing of having your heritage, you’re supposed to be, at certain times, a representative of your heritage. And then you go, “Well, what the hell is that? Who am I? One moment I’m this, one moment I’m that.” You find yourself having multiple identities. The advantage of that is you learn to get along with a lot of different people, or find commonalities with any kind of person. But at some point you have to ask, “Who am I really? And who do I want to be?” That’s what that film comes out of.

Thirty-three years later, I think I’ve figured out who I am and what I want to be. And that film was made at a time when the South Asian community was really trying to establish itself in Canada — which at that time also transmitted decidedly mixed signals around what that was and how people were received. The film talks about all of that very openly. Today, it’s a very different story. When I look at it, I say for me and I think for many of us who have been here for all our lives and call this our home, we’ve effectively made it a home and we’ve produced another generation of kids who are making it an even bigger home, and things have really changed. But at the same time, there are millions of new immigrants — because we’re a country of immigrants — and the stories in Masala keep playing out, both in reality and the kinds of content with South Asians you see on TV today. It’s the same stories that are in Masala that keep recurring. That’s what I see.

Featured Image: Wayne Bowman as Balrama (left) and Saeed Jaffrey as Lord Krishna (right)

in Srinivas Krishna’s MASALA © Divani Films Inc.

Matthew Currie

Author

A long-standing entertainment journalist, Currie is a graduate of the Professional Writing program at Toronto’s York University. He has spent the past number of years working as a freelancer for ANOKHI and for diverse publications such as Sharp, TV Week, CAA’s Westworld and BC Business. Currie ...