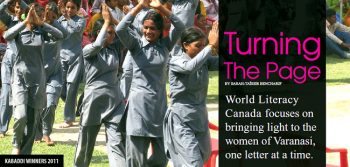

Women in the North Indian city of Varanasi mark Women's Day with a bang. And some bruises.

They are taking part in a Kabbadi Tournament put on by World Literacy Canada. Kabbadi is a rough combat team sport traditionally only played by men. But for the past three years, it’s been an allfemale tournament in Varanasi. Thousands attend the final game. The women in the tournament are part of World Literacy Canada’s (WLC) mahila mandal (women’s circle). On Women’s Day they are battling it out on the dusty Kabbadi court, but their bigger battle starts in the classroom.

These women just learned how to read.

Varanasi is in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh where 63 per cent of women are illiterate, according to WLC. Women’s literacy rates vary widely in India; the highest rates are in the state of Kerala where about 88 per cent of women are literate.

World Literacy Canada has been working in Varanasi since 1985. It was founded by a long-time American educator, Welthy Fisher, in 1955 to address India’s low literacy rates. The organization provides communities with compact Gumpti libraries (road-side stalls) full of books on anything from women’s health to cooking, as well as with educational games for children. Their mandate is to improve women’s living conditions in Uttar Pradesh through reading programs. The women form a mahila mandal for their literacy classes. WLC partners with trained local teachers to teach women life-changing skills such as reading, writing and doing simple math.

A world away, Allison Dunn is in WLC’s office in downtown Toronto, passionately sharing the organization’s goals. She is their program coordinator and spent more than five months in India as an intern, primarily in Varanasi. “Seeing how disadvantaged people are in this world was very emotional for me,” says Dunn. She snaps her fingers loudly to show how quickly she was hoping change would happen. “For me it was challenging working for the first time in an environment where I did not know the culture and the language. The cultural context was very challenging for me,” she says. But by the end of her stay, she says she came to understand and learn from this new culture and the different ways of living and working in India.

“The centre of our programs is the mahila mandal,” says Dunn, who has been to many women’s circles. “They discuss everything from finances to something that someone’s experienced that week—from abuse or something to do with their child or health. It’s a safe space to talk about important issues.”

Dunn says the women are surprised to hear that women’s abuse isn’t confined to India. “This happens in Canada, too. This happens all over the world. We’re all together in this,” she says. Improving women’s literacy is one of the ways in which WLC helps women improve their standard of living. Women in the adult literacy classes can also take part in WLC’s skills training program to help them find better paying work.

WLC provides the human and physical resources necessary to establish literacy centres for women and children in Varanasi. Their Teacher Role Model Project employs 400 women as adult and child literacy teachers to serve Varanasi’s remote communities. The women teach students and train other teachers, and are given bicycles to be able to reach these distant communities.

But alleviating women’s poverty cannot come from simply educating women, according to professor Tariq Amin-Khan, an expert in South Asian state and society and professor of politics and public administration at Toronto’s Ryerson University. Having access to education is a problem of class and not classrooms. “If you are from middle or upper classes, you will have access to quality education,” he says. “But in the rural areas [primarily lower class], it’s very different. Access to education is largely through publicly funded institutions, and it’s not universally available in every rural area.”

Non-governmental organizations like World Literacy Canada can provide educational training, funding and resources where governments have not, but the NGO model itself is limited to that extent. NGO workers come with their own values and beliefs about the way things should be, sometimes running counter to the country’s culture, and sometimes looking to enforce their own beliefs in what has been called cultural imperialism. Amin-Khan warns that it must be the local members of the communities, and not the foreign volunteers, who determine what they feel is important, where funding should go and what issues will form the basis of the curriculum. At WLC, local staff conduct a survey in the community they are newly serving to determine the women’s issues and priorities.

From their Toronto office, three full-time staff at World Literacy Canada are running programs in Canada and in India under the supervision of executive director Mamta Mishra. They help coordinate the efforts of the WLC’s off ice in Varanasi. The f ifth member of the Toronto team is a gentle, brown-eyed brown dog with fluffy ears named Abra, short for Abracadabra. WLC’s staff are passionate about their work, so it’s a fitting way to be greeted at the office—with magic.

While the crux of their work is focused on women and children’s literacy abroad, WLC also applies its principles in Canada. Every year, WLC organizes a “Big Day Out” summer camp for children living in the infamous Jane and Finch area of Toronto. The incredibly diverse neighbourhood is considered one of Toronto’s priority areas because of its high unemployment rate, lack of social services and high rate of low-income families. Nearly 30 per cent of its population has less than a high school level of education, more than double the citywide rate. Like the literacy teachers in Varanasi, the camp’s counsellors are local members of their community. They are high school students living in the neighbourhood. The camp gives the counsellors and the children the chance to go on otherwise inaccessible educational trips across Toronto, such to the Toronto Zoo and to the Art Gallery of Ontario.

This year they also organized a five-part Kama Benefit Reading Series at the Park Hyatt Hotel in Toronto. This fundraising event allowed participants to mingle with Canadian authors and to share their books and their love of reading.

At its core, World Literacy Canada is a dedicated team of individuals who realize the power of knowledge. They aren’t planning on changing the world in an instant, but they believe in their work.

“It’s nice reflecting on the successes we have had as an organization, but you just know how much more there is to do,” Dunn says.

BY SARAH-TAISSIR BENCHARIF / PUBLISHED: THE PASSION ISSUE, MAY 2011