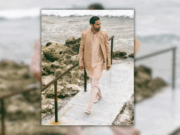

Cover Story: Art & Identity With Vivek Shraya – “My Cultural Identity Continues To Shape My Art. Sometimes, It’s Loud, Sometimes Quiet, But It’s Always There, Evolving With Me.”

Cover Stories Jun 02, 2025

June is Pride Month – a time to celebrate love, visibility, and the vibrant spectrum of LGBTQ2S+ identities. It is also a time to reflect on resilience, creativity, and the voices that push boundaries while shaping culture. Vivek Shraya is amongst today’s most poignant and powerful artists who bravely discuss and tenderly dissect identity, gender, race, and belonging. Through her deeply personal and boldly expressive work across music, literature, and performance, she offers both a mirror and a lifeline to those navigating the complexities of being seen and understood in the world.

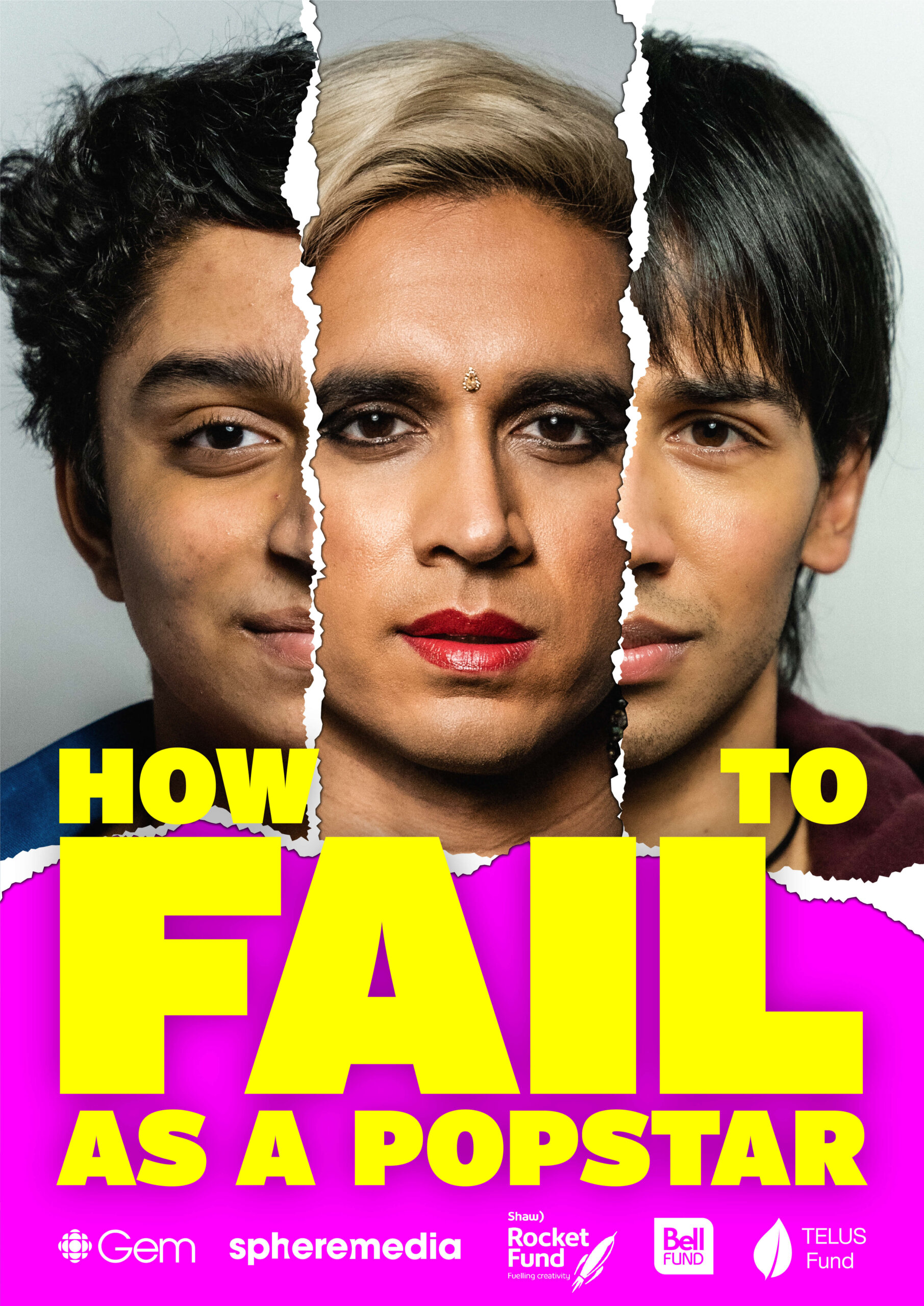

A creative force across multiple mediums, Vivek’s work refuses to be boxed in. Her artistic journey cuts across music, literature, visual art, theatre, television, film, and fashion, each discipline enriched by her bold voice and fierce authenticity. A three-time Canadian Screen Award winner, she is the creator and writer of the CBC Gem Original Series How to Fail as a Popstar, which made waves internationally with its premiere at Cannes. Vivek’s creative tapestry continues to grow from a Polaris Music Prize nomination to collaborations with icons like Jann Arden, Peaches, and Jully Black.

Vanity Fair hailed her best-selling book I’m Afraid of Men as “cultural rocket fuel,” and her influence extends beyond the arts, with brand ambassadorships for MAC Cosmetics and Pantene, guest appearances on The Social and CBC’s q, and a seat on the board of the Tegan and Sara Foundation.

Accolades

Her career is a testament to sustained creative excellence across multiple disciplines – music, literature, film, and performance. Her work has garnered over two decades of accolades, with How to Fail as a Popstar sweeping categories in 2024 (at the Canadian Screen Awards) such as Best Writing, Best Series (Fiction), and Best Actor (Comedy). The show also received international recognition at festivals including Cannes, Rio Webfest, NYC Web Fest, and T.O. Webfest, earning awards and nominations across writing, performance, music, and LGBTQ+ representation.

Beyond screen success, Shraya’s literary works have been recognized by the Lambda Literary Awards, the Alberta Literary Awards, and the Stonewall Book Awards. She has been honoured with the Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee Medal, inducted into the College of the Royal Society of Canada, and celebrated by media outlets like Chatelaine, CBC Arts, and The Globe and Mail. Her earlier achievements span music and children’s literature, with standout works like God Loves Hair, even this page is white, and I’m Afraid of Men continuing to resonate. Among her many honours, she was also named Most Promising LGBTQ Crusader by ANOKHI in 2015, reflecting her lasting impact as an artist, advocate, and changemaker.

Our Chat With Vivek Shraya

As part of our Pride Month feature, I caught up with Vivek Shraya via Zoom for an intimate and insightful conversation. Below is the exclusive Q&A, where Vivek reflects on art, identity, failure, and the evolving meaning of Pride.

Tushar: Your portfolio is nothing short of remarkable. You’ve moved seamlessly between music, literature, theatre, visual art, film, and fashion. What drives you to explore such a wide range of creative mediums?

Vivek (smiling thoughtfully): Honestly, being creative and making art gives me a reason to wake up. I need an anchor that keeps me grounded; art has always done that for me. It gives me a sense of purpose. Knowing there’s a project I’m working on, or even one waiting for me around the corner, keeps me going. That creative process is what brings meaning to my day.

Tushar: With such a diverse creative toolkit, how do you decide which medium is best for telling a story?

Vivek: Honestly, it’s a bit of trial and error. I don’t always know right away. A good example is my novel She of the Mountains. When I was working on that, I knew I wanted to create something that spoke directly to biphobia – a form of discrimination I had experienced personally, even within queer communities. I was trying to think: What’s the most effective way to challenge these misconceptions around bisexuality?

And it struck me that maybe a love story, a novel, could be a powerful approach. That’s how I arrived at the idea of writing a book. So often, I start with the message I want to convey, then ask: Which medium will express this most meaningfully? Sometimes I get it right. Sometimes, not right away.

For instance, in 2017, I released a song called I’m Afraid of Men on my album Part-Time Woman. It flew under the radar, barely anyone talked about it. But I felt I hadn’t finished saying what I needed to say. That same title later became a book, one of my most impactful works regarding audience engagement.

So now, I’m much more open to experimenting. I’ve come to enjoy not always knowing for sure. Some people will connect with the music, others with the books. The more avenues I can create for connection and impact, the better.

Tushar: Your book, I’m Afraid of Men dives fearlessly into personal and political terrain. Since its release, what reactions have stayed with you the most?

Vivek: I’ve struggled with how often people approach me and say, “I loved your book – I Hate All Men.” I know it’s meant as a compliment, but every time I hear it, it feels like the book’s point has been missed.

I’m Afraid of Men isn’t about male-bashing. It’s not a manifesto against men – it’s a meditation on the complexity of being a queer person who both fears and desires men. I was exploring the core tension: What does it mean to long for connection with men while simultaneously fearing them because of lived experiences of harm?

So when someone responds with “I hate all men,” it flattens the nuance. The book lives in that grey area where love and fear coexist. I wanted to shine a light on that duality.

Tushar: Your CBC Gem series How to Fail as a Popstar received critical acclaim and even premiered internationally at Cannes. What was it like turning your journey into a scripted show and seeing it resonate with audiences worldwide?

Vivek: Honestly, it was a very surreal experience. I think we all play that hypothetical dinner-party game, “If your life were a movie, who would play you?”, but very few people ever get actually to answer that. And there I was, writing my own story and casting actors to play me, my mom, my childhood best friend… and my ex-girlfriend. It was wild.

How to Fail as a Popstar began as a one-person play in which I performed and narrated everything from my perspective. But once it evolved into a digital series, I had to step back and let other actors embody parts of my life. Seeing those moments unfold on set – watching someone act out your childhood, heartbreaks, and dreams – was mind-blowing and profoundly moving.

I’ll say this: I probably enjoyed making the show more than any other project I’ve ever done. It was a career highlight. Even though I’ve always been a collaborative artist, most of my creative process starts with me alone at a computer. But TV is a whole other level of collaboration. You’ve got producers, network execs, directors, actors, lighting, hair, makeup – everyone gathered around a monitor, working together to bring your vision to life. It is like this magical game of make-believe.

We filmed the entire series, eight or nine episodes, in just 11 days. It was intense, but also incredibly rewarding. And then, to top it all off, getting the invitation to Cannes? That was another level of surreal. I mean, this is a story about a queer Brown kid from Edmonton, Alberta. One of my favorite moments in the show is the opening shot – a close-up of an Alberta license plate. It felt so personal, and something I’ve never seen on screen.

The irony is that the whole show is about failure – my dream of becoming a popstar that didn’t come true. And then suddenly this failure takes me to Cannes. I remember someone commented on my Instagram, “Well, that’s not a bad way to fail.” And honestly? I couldn’t agree more.

Tushar: While we’re on collaborative arts, you’ve worked with incredible artists like Jan Arden, Peaches, and Jully Black. What have these creative partnerships taught you about collaboration, vulnerability, or identity?

Vivek: Collaboration has honestly been one of the greatest gifts of my artistic journey. As a solo artist, I can get stuck whether it’s obsessing over a lyric, a melody, or a sentence in a manuscript. A lot of my books are illustrated for that very reason. Bringing another artist into the process opens up the work. Suddenly, it’s not just my story but a shared one. It deepens the meaning. It shifts what the project can say and do.

Take Jully Black, for instance. I wrote a song called “Showing Up” for How to Fail as a Popstar – it’s the closing song of both the play and the TV show. The idea behind it is simple but powerful: what do you do after you’ve failed? For me, the answer was that I still had to keep showing up. Even if I didn’t become the Brown Madonna, or tour sold-out stadiums, music is still one of the great loves of my life. I still want to make it.

And then Jully, who has her own story and relationship with fame and ambition, sings this song. She brings her entire self to it. Her voice transforms the message and adds another layer of truth. Suddenly, the song is no longer just about my failure but a shared resilience, a kind of collective endurance.

I love working with other artists. Whether it’s Jan Arden, Peaches, or Jully, each person brings their history, identity, and vulnerability. Through that, art becomes more expansive and more human. I’m always looking for ways to open my work up and invite others. Because that’s how the story grows, we all grow.

Tushar: As a South Asian artist, how has your cultural identity shaped your creative voice and the stories you choose to tell?

Vivek: It’s definitely shifted over time. When I started making music at 23, I was incredibly anxious about being boxed into the “world music” category. In Canada, the music industry hasn’t historically left much room for South Asian artists, especially those making English-language pop that isn’t rooted in traditional South Asian sounds. There’s a lot of interest now in Bhangra and Punjabi music, which is fantastic, but if you’re a South Asian artist making pop music that doesn’t sound South Asian, it confuses people.

I remember releasing my first album, and people would say, “Oh, I can hear the Eastern influence.” But there was no tabla, no sitar. You would still say that if you didn’t know what I look like. There’s this impulse to classify art based on the artist’s appearance rather than the work itself. So, in those early years, I deliberately avoided being overtly South Asian in my work. I didn’t want to be pushed into a box that didn’t fit. I remember going to HMV and seeing that all white artists were labeled “pop,” Black artists were “R&B,” and everything else – South Asian, East Asian, Latinx – was just dumped into “world music.” But I wasn’t making “world music.” That label didn’t reflect what I was doing.

Then, when I started writing books, I felt a shift. With my first book, it felt important to talk about my Indian identity, especially as someone who grew up in Canada. I began to embrace that part of myself more overtly. I also wrote about Hinduism in the early stages of my writing career. As a queer kid, Hindu iconography was a lifeline for me. In the absence of queer role models, I saw myself in the gods, Krishna with his long hair and love of music, Shiva surrounded by feminine energy. I didn’t relate to North American masculinity, but I saw something softer, more fluid in Hindu mythology. It was validating.

I wanted to honor how much that mythology gave me. But over time, I became more aware of how Hindu nationalism has contributed to the marginalization of Muslims and the rise of Islamophobia. And so, as a gesture of solidarity, I’ve pulled back from exploring Hinduism in my work. That doesn’t mean I’ve rejected that part of myself, it’s still there, subtly, in everything I do. But I’m more thoughtful now about when and how to lean into that identity, depending on where I am in my journey.

So, yes, my cultural identity continues to shape my art. Sometimes, it’s loud, sometimes quiet, but it’s always there, evolving with me.

Tushar: Yes, representation is powerful, especially in mainstream media. What does authentic queer South Asian representation look like to you, and how do you feel it’s evolving in Canada and globally?

Vivek: That’s a tricky question because I don’t think there’s a single, universal answer. When people talk about authenticity, I often struggle with the term – it tends to imply something fixed or final, like there’s one true version of who we are. But I don’t believe in singularity; I believe in multiplicity. I believe in evolution.

For me, authentic queer South Asian representation is simply who I am at a given moment. What felt genuine to me in my twenties looked very different in my thirties, and now, in my forties, it’s evolved again. So, I approach authenticity as fluid, not something that can be pinned down or defined once and for all.

That said, I’ve always created work with a clear feminist agenda. I want my work to celebrate femininity and push back against misogyny. I also want it to celebrate brownness – my own and others’. That means representing brown skin on screen or on the page and making a conscious effort to collaborate with other BIPOC artists. Those are core values that guide me.

But even those values are part of a larger, ongoing process. There’s no singular, ultimate version of “authentic queer South Asian representation” for me, it shifts with time, experience, and awareness. What matters most is that the work stays rooted in care, community, and a commitment to growth.

Tushar: Have you faced challenges or expectations within the South Asian community as you built your career? If so, how have you navigated those experiences?

Vivek: Definitely. One of the things I’ve found challenging, especially in Toronto, where I’ve spent most of my life, is that there doesn’t seem to be a cohesive South Asian community. It often feels fractured. I feel pretty disconnected from other South Asians outside of my personal friend group or the artists I admire.

Part of that may be because the term “South Asian” itself is so broad. It includes people from various regions, languages, religions, and cultures. Maybe it’s challenging to build a unified community when the umbrella is so broad.

That said, I have certainly encountered both support and resistance from South Asians. Some have been incredibly affirming of my work, but others have kept their distance – whether that’s due to my queerness, my trans identity, or perhaps the themes I explore. That kind of selective support can be painful. You want to feel embraced by your community, especially when your work is deeply tied to identity.

Sometimes I look at cities like Vancouver, and maybe I’m romanticizing, but there’s a more vibrant, interconnected South Asian presence there. People seem to be finding each other and creating something meaningful. I haven’t felt that as strongly here, and I wish I had more of that sense of connection. It’s something I continue to long for.

Tushar: You’ve also served as a brand ambassador, guest host, and a voter director. How do you choose projects that align with your values, and how do you stay grounded while doing so much public-facing work?

Vivek: That’s a great question I often wrestle with. We live in a time of influencers, content creation, and brand partnerships. And I have zero judgment for folks doing that kind of work. It’s not easy, and if that’s how you’re making a living, I fully respect that.

But for me, I’ve always seen myself first and foremost as an artist. I don’t make “content.” My work isn’t designed to be consumed in 30-second bites – it asks for engagement, for attention. And I get that it can feel outdated in today’s fast-paced world. Sometimes I feel like an old model in a new system. But that’s who I am.

Regarding collaborations, I consider whether the project aligns with me and my art. Take MAC, for example, that was my first brand partnership, and it was an easy yes. I had recently transitioned, and MAC was the only makeup I used. It felt organic, I wasn’t selling something I didn’t believe in or use myself.

The same goes for Pantene. Hair has always been a big part of my personal expression, and it appears repeatedly in my work – my first book was even titled God Loves Hair. So that partnership made sense on a deeper level, too.

That said, to be completely transparent, compensation also matters. I’ve had a day job for most of my career. Making art, whether it’s albums, books, or performances, is expensive. I rarely work on just one thing at a time, so I’m constantly trying to figure out how to fund it all. Sometimes a brand deal gives me the resources to keep creating and supporting others. I try to reinvest whatever I can into communities and causes that have less than I do.

So, in the end, it’s a bit of a complex equation: Is this aligned with me as an artist? Will my audience understand the connection? And will this help me continue to make the kind of work that matters to me – and, hopefully, to others?

Tushar: Your work often bridges art and activism. Do you see art as a form of advocacy? And how intentional are you about blending the personal with the political?

Vivek: That’s such a thoughtful question. Do I see art as advocacy? In many ways, yes, but I also have complicated feelings about how my work is received as political. I think any time you create from a personal place, and you’re not white, or not straight, or not cis, your work is immediately labeled as political or about “identity.” And that framing can be frustrating.

All art is, in some way, about identity. But when it comes from a marginalized voice, that label is rarely meant as a compliment. More often, it’s a way to categorize and, frankly, minimize what BIPOC artists are doing. It creates a box, and people expect you to stay there once you’re in it.

Now, some of my work is intentionally political. I’m Afraid of Men is a clear example. That book was a deliberate exploration of misogyny and patriarchy. I wanted readers to examine their relationships to those systems. So yes, there was advocacy in that project.

But sometimes I create things that aren’t overtly political, and they still get read through that lens. Or worse, they get overlooked. One of the most challenging projects I’ve put into the world was, believe it or not, a children’s book about raccoons. And while kids’ books about animals are everywhere, publishers didn’t understand why I, someone they associate with politics and identity, would want to write something so “light.” That kind of reaction speaks volumes about how limited the industry’s perception of artists like me can be.

I care deeply about justice and equity. I do want to contribute to a better world through my art. But I also want the freedom to explore whatever themes speak to me – whether that’s pop culture, nature, or yes, even raccoons. My hope is to keep pushing for that kind of creative autonomy, while staying grounded in my values.

Tushar: What’s next for your creativity? Are there any upcoming projects you’re excited to explore?

Vivek: Yes! I’m launching a new short film this week called Body Rebuilding at the Inside Out Queer Film Festival here in Toronto. It’s about my experience managing chronic pain through discovering weightlifting. For me, chronic pain conversations often focus on the idea that there’s something “wrong” with your body, like you’re not stretching enough or you’re just aging. But I wanted to explore a broader perspective: how our environment and circumstances play into those experiences. I’m excited to share this film and have been pitching it to other festivals, so hopefully it will reach broader audiences.

On the music front, I have a new album called New Models coming out in October. Before that, I’m doing a preview show in Toronto on June 6th, which I’m looking forward to. I’ll also perform at the Indian Summer Festival in Vancouver in July and tour the album in the fall. So, there’s a lot of live music on the horizon, which is always thrilling.

And on top of all that, I’m working on my 13th book, my third novel, a science fiction dystopian story set to be published by McClelland & Stewart next fall. So, it’s shaping up to be a big year with some inspiring projects across different mediums.

Tushar: June is Pride Month. What message or reflection would you like to share with younger queer South Asian artists who are just beginning to find their voice?

Vivek: I would say that especially right now, with everything happening – the increased surveillance, the rise in hate directed at queer and trans people – it’s understandable that some might feel the urge to pull back or stay quiet out of fear. And that fear is very real and valid. But I genuinely believe this is when our voices matter the most. It’s time to keep creating, telling our stories, and sharing our art with the world in whatever way we can. That act of expression, especially now, is powerful and necessary. So, to anyone starting, I want to encourage you to lean into your creativity, it’s a vital part of who we are and how we make change.

Tushar: Now, I’d like to play a fun-ending rapid-fire game with you if you’re open to it.

Vivek: Let’s play!

Tushar: Great! There are two sections. The first is called I AM… When I say, “I AM aware of _________,” you complete the sentence with whatever first comes to mind.

Vivek: Okay… I’m aware of… hmm, you want me to answer that now? Oh wow, I thought this would be easy! Why is this so hard? Can we come back to this one?

Tushar: Sure! No pressure. Just say whatever pops into your head. Let’s try another: I AM fearful of ________.

Vivek: I AM fearful of not doing enough.

Vivek: I AM angered by… uh… complacency.

Vivek: I AM in love with my partner.

Vivek: I AM best at creating.

Vivek: Um, I’m shy of… hmm. Can we come back to that one too?

Vivek: I AM always ready for… popcorn.

Tushar: Okay, let’s revisit the others.

Vivek: I AM aware of… a new Netflix show with Julianne Moore.

Vivek: I AM shy of… how much TV I watch.

Tushar: (laughs) That was fun! Okay, next section: FOR ME…

I’ll say, “FOR ME, _____ is _______,” and you finish the sentence.

Vivek: Let’s do it!

Tushar: FOR ME, excitement is _________.

Vivek: FOR ME, excitement is seeing a movie in IMAX.

Vivek: FOR ME, confusion is… other people’s hatred of difference.

Vivek: FOR ME, prejudice is… a waste of time and energy.

Tushar: Absolutely.

Vivek: FOR ME, peace is… a free Palestine.

Vivek: FOR ME, hope is… meeting young queer and trans youth.

Vivek: FOR ME, satisfaction is… completing a project or realizing an idea.

Vivek: FOR ME, loyalty is… having a conversation when tension emerges.

Vivek: FOR ME, friendship is… (pauses) evolving.

Vivek: FOR ME, love is… reciprocal.

Tushar: Beautiful. I enjoyed this rapid-fire, especially seeing how honest and thoughtful your responses were on the spot. Thanks so much for taking the time to chat with me.

Vivek: Of course! Thank you so much.

As our conversation with Vivek draws to a close, what stands out most is her courage and authenticity in her art and life. Navigating the intersections of identity, politics, and creativity, she reminds us that art is both a personal journey and a powerful form of advocacy. Whether tackling weighty social issues or simply celebrating the joy of raccoons, Vivek’s work challenges us to embrace complexity and find freedom in our creative voices.

Her words resonate deeply, especially during Pride Month, when she urges younger queer South Asian artists to persist despite adversity: now more than ever, their stories matter. Vivek creates and inspires us through her films, music, writing, and activism, showing us the transformative power of honesty, hope, and resilience.

Thank you, Vivek, for sharing your insights, vulnerabilities, and boundless creativity. We look forward to witnessing the following chapters of your incredible journey.

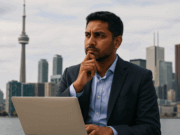

Author

Internationally celebrated, award-winning media personality and author of several business and lifestyle articles, Tushar Unadkat, is the CEO, Creative Director of MUKTA Advertising, Founder, and Executive Director of Nouveau iDEA, Canada. He holds a Master of Design from the University of Dundee, S...