Is your marriage doomed by cultural demands?

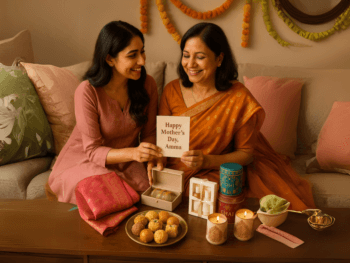

Neha and Deepak (real names not used) met in university, fell in love and got married. Everything seemed splendid. But a year into their marriage, things started to get hazy.

“For one thing, we didn’t live together before we were married,” Deepak said. “How was I supposed to know she had a 30 minute session in front of the mirror every morning! We are always late to everything because of her.”

“He’s no walk in the park either. He refuses to do anything in the kitchen—no cooking, no dishes. I mean, come on,” Neha retorts. “He is a pampered brat. Mommy did everything for him.”

“Like every other Indian male, he feels entitled to women serving on him hand and foot.”

“Oh yeah, well, your mother (calls) every day, sometimes three to four times. And we are expected to drop everything for her, but you never help out with my parents,” he shoots back. “Why does (your mum) get a say in how we manage our lives?

Sounds familiar?

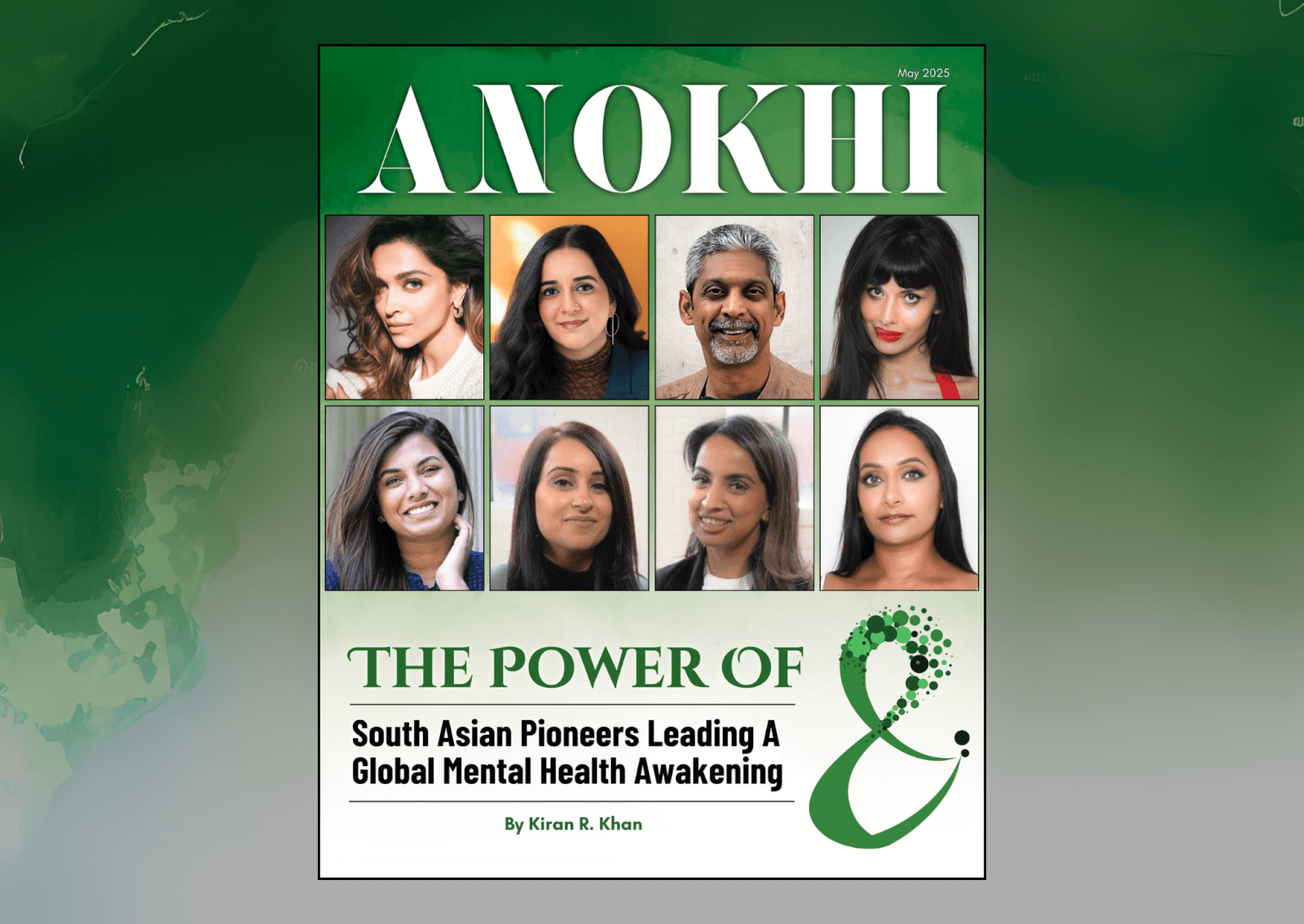

“I know it sounds cliché, but the first complaint for at least 70 per cent of South Asian couples is extended family,” says therapist Saunia Ahmad of Toronto-based South Asian Couples Counseling. The organization offers short-term therapy for those who don’t want to be pigeonholed into Western solutions.

That being said, Ahmad believes that in many cases, a couple facing difficulty might externalize problems in their own relationship by placing blame on an outside factor, such as parents. South Asian couples are no different than any other couples worldwide.

“We’ve seen issues over how your kids are being raised, dividing up household chores, affairs, career-related issues,” Ahmad says, who has experience counseling 40 South Asian couples. “But sometimes those cultural nuances are missed.” Ahmad notes that there's simply a lack of counseling services for ethnic couples.

"Going to couples therapy isn’t something that is really done among South Asians, but many of the couples that we have dealt with say they are glad that we do the work we do,” she says. “Some people won’t seek out treatment because they feel they're stereotyped, they don't feel people will understand their culture. Or sometimes it’s just a language barrier."

“The key is communication and we do that by getting the couple to really listen to each other,” Ahmad says.

“I wish I could tell him why family is so important to me,” says Payal, a second generation Bengali. She’s dating Jack, a through-and-through white Canadian (real names not used).

“Her family put insane amounts of pressure on her—what she studies, when she can go out,” Jack said. “Why is she studying medicine when she wants to do something else?! Sometimes, their demands are so unreasonable that I’m surprised she just doesn’t cut off all contact with her crazy extended family. I really do try and understand, but seriously, if my parents acted that way, I would just leave.”

But Payal feels that is not an option. As the eldest child, she feels obliged to listen to her parents.

“They don’t even really approve of me dating Jack, but at least, you know, they agreed to meet him,” she said. “And I can’t just leave them. It’s just not the done thing.”

The choices of second generation South Asians are most interesting, says Rifat A. Salam, a professor of sociology at the City University of New York. Does the quest for true love conflict with traditional values? Is assimilation into North American culture even possible if you want to maintain ties with your cultural heritage? These are the kinds of questions that Salam is studying.

“There is definitely a gender bias, particularly for female children whose parents have high expectations of academic and career success but equally high expectations of obedience and deference to parental authority,” she says. At the root of this issue is the notion that parents are always the head of the family, even for adult children, who are expected to consult and defer to their parent’s judgment.

“Second generation South Asians, who were raised in an external environment which teaches and encourages autonomy, are torn by the conflict between familial obligations and their personal desires,” Rifat says. She notes that arranged marriage, in the strictest sense, is on the decline and “love marriages” do occur but endogamy is still the norm.

"There are so many myths about second generation South Asians and arranged marriages. I wanted to look at the reality."

In her study, “Beyond Assimilation: Autonomy and Gender in the Second Generation South Asian American Experience,” Salam interviewed a number of South Asians to discuss what influenced their marital choices. She divided the respondents into three large categories:

The traditionalists, which comprised 55 per cent of the study, believe that a partner of similar religious and ethnic background will have similar values, and thus would likely be the most compatible partner. An example from the study would be Chandan, a 36-year-old surgeon from India.

“You want to marry someone who has the same values as you do and who you have things in common with. You’re also going to have less conflict about things, especially when it comes to children. You don’t have to worry about what religion or culture to raise them with. Sure, I liked to party a lot when I was younger and went out with a lot of girls, but when it comes to marriage, that’s serious.”

Then there are those who follow the independent pathway, roughly 35 per cent of all respondents. These folks will work both systems, be it through mainstream dating methods or set-ups made by relatives. Some of them even joke that their non-South Asian friends wish they had similar opportunities.

The last group and also the smallest at 10 per cent are the ethnic rebels. This group tends to reject any association with their community, perhaps due to prior negative conservative experiences. For example, a woman might feel repressed by her father or a suitor who would forbid her from working after marriage.

Salam says that understanding how second and third generations approach marriage is key to understanding how these groups see them assimilating into a North American framework.

“I think many South Asian Canadians are seeing themselves in a new context. They are not necessarily living in a joint family, but they still want to function as one,” Ahmad said.

“They feel like as if they have to choose between their parents and the North American approach, but we want to provide them with a third option—communication.”

She says the core to a couples’ success is to "think" in terms of a unit, or “we,” rather than “you versus I.”

“Many partners automatically, without always realizing it, think and make decisions based on their own perspectives,” Ahmad says. “We want to get them past that . . . to appreciate that there will always be difference.”

Opposites do attract and no one wants to marry someone who thinks and feels exactly like his or herself.

“They key ingredient to a healthy marriage is to find ways to value and embrace differences, not just simply tolerate them,” she says.

If you are interested in South Asian couples counseling, please visit www.southasianfamilies.com

BY: TAMARA BALUJA / PUBLISHED: MAY 2010 ISSUE

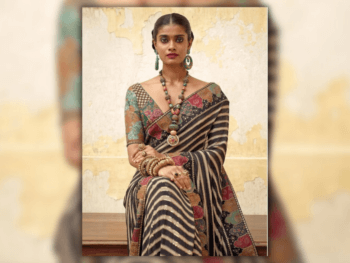

(PHOTO BY FOTOLIA.COM)